The Council of Industrial Design, started on December 19, 1944 as the Council of Industrial Design was founded by Hugh Dalton, in the wartime Government. And its objective was 'to promote by all practicable means the improvement of design in the products of British industry'.

S. C. Leslie, the Council's first director, played an important part in the ''Britain can make it'' exhibition of 1946. It was 1947 successor Sir Gordon Russell who established the organisation's model for the next 40 years. Under Sir Paul Reilly in the early '70s, the organisation changed its name to the Design Council in 1972'' . 'Britain Can Make It' exhibition, organised by the Council of Industrial Design was a showcase for British design and manufacturing, and was a precursor to the more widely celebrated Festival of Britain in 1951.The aim was to display the latest consumer goods and promote the best of British design and industrial production. The exhibition occupied some 90,000 square feet of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and attracted 1,432,546 visitors. It contained over 5000 items produced by British manufacturers and encompassed most types of consumer goods including furniture, tableware, domestic appliances, household equipment, carpets, wallpapers, clothing and toys. Britain Can Make It did not adopt the traditional format of a trade exhibition, in which companies bought space to display whatever they wished. Instead, the CoID itself selected all the items that were displayed, and in doing so it used the exhibition to promote its own particular notion of 'good design' the CoID rejected redundant ornament and the superficial 'styling' of objects in favour of plain, ostensibly functional forms that embodied an efficient use of appropriate materials.

|

| Britain Can Make It', colour lithograph poster advertising the exhibition organised by the Council of Industrial Design, held at the Victoria and Albert Museum, 24 September – 31 October 1946, designed by Ashley Havinden, Great Britain, 1946, CIRC.459-1971. Victoria and Albert Museum, London. |

|

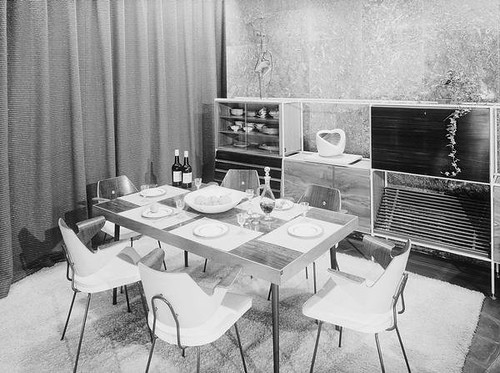

| Living room setting at the 'Britain Can Make It' exhibition, 1946 |

|

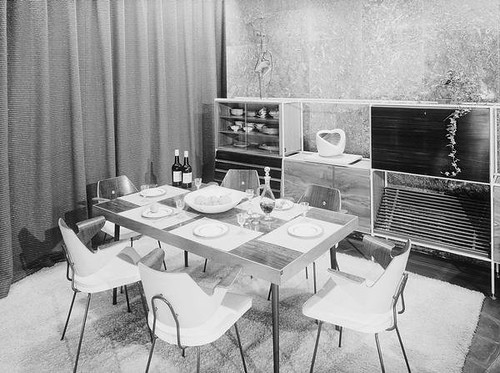

| Furnished living room at the 'Britain Can Make It' exhibition, 1946 |

|

| Prototype electric bicycle displayed at the 'Britain Can Make It' exhibition, 1946 |

|

| Three kettles included in the 'Britain Can Make It' exhibition, 1946 |

The Festival of Britain

|

The Festival of Britain emblem, designed by Abram Games, from the cover of the South Bank Exhibition Guide, 1951.

The logo uses the traditional red, white and blue colours of the Union Flag. The main device incorporates a profile of Britannia's head, with crested helmet, on the "north" point of a four-pointed compass rose Games added a row of bunting flags to his first design concept when asked to make it more festive. The anticlockwise halves of each compass point are coloured, with the clockwise halves white: the "east" and "west" points are red and white, and the "north" and "south" points (including Britannia's head) are blue and white. The figures "19" in blue and "51" in red appear in the lower left (SW) and right (SE) quadrants, with quarter circles of bunting below connecting the "south" compass point to the "east" and "west" points, with six flags either side of the "south" point and a pattern of four flags (white, red, white, blue) repeated three times. A version used on official publications places the logo on a background quartered in a background colour and black, surrounded by four additional compass points. |

The original idea for the Festival of Britain emerged in 1943, when the Royal Society of Arts proposed that something should be done to commemorate the centenary of the Great Exhibition of 1851. After the war the government took up this proposal, but instead of attempting to stage another major international exhibition it decided to organize an event that would instead celebrate 'the British contribution to civilization, past, present and future, in arts, science and technology, and in industrial design.' At that time, shortly after the end of World War II, much of London was still in ruins and redevelopment was badly needed. The Festival was an attempt to give Britons a feeling of recovery and progress and to promote better-quality design in the rebuilding of British towns and cities.

Although the main site of the festival was in London, the festival was nationwide affair with exhibitions in many town and cities throughout Britain.After the devastation and resulting austerity of the war years, the Festival of Britain aimed to raise the nation's spirits, whilst promoting the very best of British art design and industry. The event was considered a ''Tonic for the nation'' . Festival of Britain portray the country as a modern pioneer. It was the first major world event to be televised. Watched by millions across the Globe.

The most important festival site was the South Bank of the Thames. The Festival transformed it from a site of Industry to a place of culture and the arts. New structures were built to house the exhibitions exploring Britain's landscape, The British character, British industry and science. Although the Festival took pride in Britain's past, most of the exhibitions looked to the future. science and technology featured strongly. The structures included a new concert hall- "The Royal Festival Hall", "The Dome of Discovery" which was the largest dome in the world at the time, standing 93 feet tall with diameter of 365 feets, and the astonishingly slender - "Skylon", iconic and futuristic-looking structure; It was unusual, vertical cigar shaped tower, supported by cables that gave the impression that it was floating above the ground. All of these new building were concidered radical and new. No one had seen design and architecture like this. In keeping with the principles of the festival, a young architect aged 38, Hugh Casson, was appointed director of architecture for the Festival and to appoint other young architects to design its buildings.

Over the summer of 1951 The Festival of Britain was everywhere: in shops, events, exhibitions, radio programs and concert halls. In one of the pavilions, many Londoners saw their first ever television pictures. By september 1951, over eight million people had visited the South Bank exhibition.

As with most large Government sponsored and funded projects (the Millennium Dome, London 2012), the Festival met much controversy, from the concept to completion. Even before the Festival opened, the Festival was condemned as a waste of money. Many people believed it would have been better spent on housing after the destruction of many houses during the Second World War. Once opened, the critics turned to the artistic taste; the Riverside Restaurant was seen as too futuristic, the Royal Festival Hall seen as too innovative and even certain furnishings in the Café met criticism for being too gaudy. It was also criticized for being too expensive, with entrance to the Dome of Discovery at five shillings. Even with the above complaints the main Festival site on the South Bank managed to attract more than 8 million paying visitors.

Always planned as a temporary exhibition, the Festival ran for 5 months before closing in September 1951. It had been a success and turned over a profit as well as being extremely popular.

|

| A view of the South Bank Exhibition from the north bank of the Thames, showing the Skylon and the Dome of Discovery |

|

| Aerial view of Festival of Britain, 1951. painting |

|

| The Dome of Discovery and Skylon, 1951 |

|

| Skylon |

|

| Exterior view of part of the Festival of Britain site 1951, showing 'Antelope' and 'Springbok' chairs designed and made by Ernest Race Ltd. The Festival of Britain promoted the outside coffees witch were quite unusual for Britain. People didn't sit outside because of the air pollution from the use of coal which formed a thick layer of smog over the city. |

|

| Festival of Britain, Homes & Gardens Pavilion. Designed by Robin and Lucienne Day with Barbara Hepworth sculpture. Mid-class apartment. |

The 1951 Festival of Britain brought together artists and architects in a celebration of British culture which looked to the future as well as the past. Misha Black, one of the principal organisers of the Festival, later wrote: 'Those of us who were responsible for the design of the exhibition set ourselves two objectives. The first was to demonstrate the quality of modern architecture, landscape architecture and town planning; the second to show that painters and sculptors could work with architects and exhibition designers to produce an aesthetic unity.' (quoted in Banham and Hillier, p.92) One of the buildings constructed for the exhibition was the Riverside Restaurant, designed by Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, who approached Nicholson in June 1950 to paint a mural for the entrance.

|

| Ben Nicholson OM 'Festival of Britain Mural', 1951 |

|

| Contrapuntal Forms on London's South Bank during the Festival of Britain, Designed by Barbara Hepworth, 1951. Hepworth's first public commissions were for the Festival of Britain. Contrapuntal Forms (1950–51, Irish blue limestone, 120 inches in height) was commissioned by the Arts Council to stand on the South Bank during the Festival. Hepworth carved the two monumental figures in Irish blue limestone with the help of assistants |

|

| Boric Acid 8.34 Wallpaper John Line and Sons, part of the Festival Pattern Group, a scheme in which 28 manufacturers drew on the emerging science of crystallography to develop new pattern designs that were applied to fabrics, wallpapers, carpets and other products. |

|

| Insulin 8.25 Wallpaper John Line and Sons |

|

| Haemoglobin James Templeton & Co |

|

| Vitra Multi Coloured Ball Clock By George Nelson. Designed in 1948 during a huge U.S. economic boom, Nelson's vision was to bring modern lasting design into common aspects of the home. This re-edition clock is manufactured and distributed by Vitra Design Museum, Germany, using original models and documents from the George Nelson archive. |

|

| Shown is 'Calyx',Designed by Lucienne Day, originally designed for Festival of Britainin 1951. Available in maroon, yellow, grey and charcoal. |

We were asked what would we design for the festival of Britain. I came out with the idea of desk lamp in the shape of Skylon. Here's my sketch :